PEP 6305 Measurement in

Health & Physical Education

Topic 8:

Hypothesis Testing

Section 8.2

Click to go to

back to the previous section (Section 8.1)

Click to go to

back to the previous section (Section 8.1)

Effect Size (pp. 164-166)

n

The effect size is a measure of how much the

treatment changed the dependent variable.

¨

In the example above, the conclusion was that regular aerobic

exercise “had an effect” on serum cholesterol.

·

Did aerobic exercise raise or lower serum

cholesterol levels?

·

By how much did exercise raise or lower serum cholesterol

levels?

¨

These types of questions are answered by measures of effect size.

n

Effect size is one way to judge whether the effect or association

has any practical meaning or use.

¨

It is possible to have a “statistically significant” (“p < 0.05”)

result that actually has little practical value (see the green box at left).

n

Many effect size measures exist. These measures are generally

grouped into two common types:

¨

Standardized mean difference. This type of effect size

describes the difference in two means divided by the standard deviation of the

population (or control group), and can be interpreted similar to a

Z-score.

·

A standardized mean difference is the difference stated in SD

units (the number of SDs separating the means).

·

On textbook page 165, “Effect Size” (ES) and “percent improvement” are

both standardized mean differences. ES is standardized to the SD of the population,

and percent improvement is standardized to the respective baseline value.

¨

Magnitude of association. This type of effect size

describes the

proportion of variance that the effect accounts for in the

population, and can be interpreted similar to how R2 is

interpreted.

·

On textbook page 165, omega squared (ω2) is a proportion

of variance.

n

How big “should” the effect size be? There are several common

approaches to interpreting effect size. The following are listed from the

strongest to the weakest approaches.

¨

First: The effect size can be compared to effect

sizes in the published literature from studies of the same

measure of the dependent variable in the same population under

the same conditions. The effect size in your study can then be

interpreted in relative terms (bigger, smaller, etc.) to other known effects.

·

However, finding studies with the same measure of the dependent

variable in the same population under the same conditions as your study may be

difficult.

¨

Second: The effect size can be compared to effect

sizes in the published literature from studies of the same or a

similar measure of the dependent variable or a similar

variable in the same or a similar population under the same

or similar conditions. The effect size in your study can then be

interpreted in relative terms (bigger, smaller, etc.) to these effects.

·

However, the more dissimilar studies become in terms of measures,

variables, population, and conditions, the more difficult it is to justify

comparing the respective effect sizes.

¨

Third: The effect size can be compared to other

data collected during the study. For example, a study of increasing lower

leg strength in elderly people finds a statistically significant change after resistance

training. The authors report a percent improvement of 15%. Is 15% a large or

small improvement? Suppose that none of the subjects could ascend a flight of

stairs before the training, but all could by the conclusion of the study. These

additional data are helpful; a 15% change in lower extremity strength in elderly

subjects was associated with a large effect on function.

·

However, this type of interpretation relies on solely on

information collected from one particular sample; the effect may or may not have

the same magnitude or associations in the population.

¨

Fourth: The effect size can be interpreted using

general guidelines. For example, the ES statistic is often described as

“small” when the value is around 0.20 and “large” when it exceeds 0.80. These

are general guidelines that may not be accurate in some studies.

·

Using these general guidelines should, in my opinion, be a last

resort. They essentially represent a guess that is based on virtually no

information about the variable, population, or conditions being studied.

n

In general, both the

error probability and an

indication of effect size should be reported, particularly when presenting

“statistically significant” results.

¨

The error probability provides the probability that the data were

a result of sampling error. A low error probability (e.g. ≤0.05) means that the

data were unlikely to be a result of sampling error. In other words: there was

an effect.

·

Error probability does not provide any indication regarding the

magnitude, importance, or meaning of the effect.

¨

The effect size provides a measure of the magnitude of the effect.

·

The magnitude can often be used to evaluate the importance or

meaning of the effect.

n

I will mention effect sizes in subsequent course Topics that

discuss various types of statistical tests.

¨

For example, the typical effect size reported for t tests

is a statistic called Effect Size (ES, also known as Cohen’s d):

As

discussed above, interpreting ES is similar to interpreting a Z-score.

As

discussed above, interpreting ES is similar to interpreting a Z-score.

¨

Omega squared (ω2), the proportion of variance

in the dependent variable that is explained by the independent variable, is

occasionally reported for t tests.

·

The formula for ω2 is on page 165. You do not

need to memorize this formula, but remember it is conceptually similar to the

R2 value we discussed in

Topic 6.

Type I and Type II Errors (pp. 166-167)

n

A statistical hypothesis test either rejects the null

hypothesis or fails to reject the null hypothesis.

¨

Rejecting the null hypothesis supports your research hypothesis.

¨

Failure to reject the null hypothesis means you have no support

for your research hypothesis.

n

Four things can happen in hypothesis testing:

¨

The null hypothesis is rejected, and in reality it is false.

·

This is a correct decision; if the null hypothesis is false, it

should be rejected.

¨

The null hypothesis is rejected, but in reality it is true.

·

This is an incorrect decision—an error, because you have rejected

a statement that is true.

·

This is a type I error. Type I error is what error

probability alpha (α) estimates.

¨

The null hypothesis is not rejected, and in reality it is

true.

·

This is a correct decision; if the null hypothesis is true, it

should not be rejected.

¨

The null hypothesis is not rejected, and in reality it is

false.

·

This is an incorrect decision; if the null hypothesis is false, it

should be rejected.

·

This is a type II error. Type II error is estimated by a second of

error probability called beta (β).

n

You will never know for certain whether the null hypothesis

is true or false; consequently, you will never know for certain whether

your decision is right or wrong.

¨

The probabilities indicate how many times you would be right (and

wrong) if you repeat the exact same study many (>1000) times over.

n

This table demonstrates the relation between the statistical

decision and reality in hypothesis testing:

|

|

|

REALITY |

|

|

|

Null is True |

Null is False |

|

STATISTICAL DECISION: |

Do Not Reject Null |

1 – α

Correct |

β

Type II error |

|

Reject Null |

α

Type I error |

1 – β

Correct |

¨

The symbols in each cell of this table (α and β) are

probabilities.

¨

Note that the Reality columns are mutually exclusive;

either the null is really true or it is really false (it can't be both).

·

Because of this, the values in the first column are unrelated to the

values in the second column .

¨

Probabilities range between 0 and 1.00. Each column has only two

possible outcomes. The sum of each column = 1.00.

n

If you do not reject the null hypothesis (first

row), either:

·

The null is true, and your decision is correct

(first row, first column). This probability is 1 – α.

·

The null is false, and your decision is wrong (first

row, second column). Beta (β) is the Type II error probability. β is the

probability that you have an unusual sample that has produced an extreme value

for the statistic when the population value is actually equal to the null

condition.

n

If you reject the null hypothesis (second row),

either:

·

The null is true, and your decision is wrong (second

row, first column). Alpha (α) is the Type I error probability, the probability

that the data are a result of sampling error alone.

·

The null is false, and your decision is correct

(second row, second column). This probability is 1 – β (see

Power and Sample Size

in the next section).

n

Common values for α and β are 0.05 and 0.20, respectively.

Thus, regardless of reality:

¨

The probability of being wrong when you do not reject

the null is α = 0.05 (5%). (Type I error)

¨

The probability of being correct when you do not reject

the null is 1 – α = 1 – 0.05 = 0.95 (95%).

¨

The probability of being wrong when you reject the

null is β = 0.20 (20%). (Type II error)

¨

The probability of being correct when you reject the

null is 1 – β = 1 – 0.20 = 0.80 (80%).

n

These probabilities are most important when designing a study,

before data have been collected.

¨

Investigators specify these probabilities for making correct

decisions before they have actually done the study.

¨

The investigator can decide the relative importance of the two

types of error, and design the study accordingly.

·

If a new treatment is expensive, time-consuming, or painful, we

would want to be very sure that it actually works a lot better than the standard

treatment before we recommend it. In this scenario, we can design the study to

“protect against a Type I error” by setting α to lower value (say, α = 0.01

instead of α = 0.05).

·

By contrast, if very small effects are important, we want to make

sure we detect such small changes when they actually exist. In this scenario, we can

design the study to protect against a Type II error by setting β to a lower

value (say, β = 0.05 instead of β = 0.20).

¨

For a given sample size and set of conditions,

increasing α decreases β, and increasing β decreases α.

·

Minimizing both α and β (i.e., minimizing both

types of error) is expensive (see

Power and Sample Size

in the next section), and often

unncecessary because one type of error is usually more important that the other

for any given study.

·

Thus, the consequences of making either error should be

weighed carefully so the study minimizes the wrong decision that has the most

consequences.

n

Some possible causes of each type of error are listed on page 144

of the text.

¨

What contributes to both types of error?

Two-Tailed (Non-Directional) and One-Tailed

(Directional) Tests (review pp.99-101 from Ch. 7)

n

Recall (or go back and review) the discussion of

hypothesis

testing in Topic 5, particularly the computation and interpretation of error

probability.

¨

Topic 5 had a simplified explanation of hypothesis

testing.

¨

However, there are actually two types of null hypotheses

that require slightly different statistical testing methods.

n

The two types of null hypothesis are:

¨

Non-directional null hypotheses simply state that

there will be no difference from the comparison condition. The non-directional

research hypothesis states that there will be “a difference,” but whether that

difference will be an increase or a decrease in the dependent

variable is not stated. Either type of difference would support the

research hypothesis.

¨

Directional hypotheses specify the type of

difference from the comparison condition. One type of difference in a directional

research

hypothesis is a decrease in the dependent variable relative to the

standard; the corresponding directional null hypothesis is equal to or

greater than the standard. The other type of directional difference is greater

than the standard. What is the corresponding null hypothesis

for this directional research hypothesis?

·

For example, suppose you are investigating whether young girls

(ages 8 to 10) are heavier than boys of the same age (since girls progress to

physical maturity at an earlier age). Your (directional) null hypothesis is that

the body weight of the girls is equal to or less than the body weight of

the boys. Your (directional) research hypothesis is that the girls will weigh

more. You are not interested in testing whether the girls weigh less

than the boys, only if the girls weigh more.

·

How would you state the non-directional null and research

hypotheses for comparing the weights of girls and boys?

n

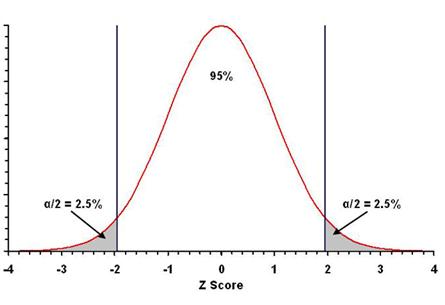

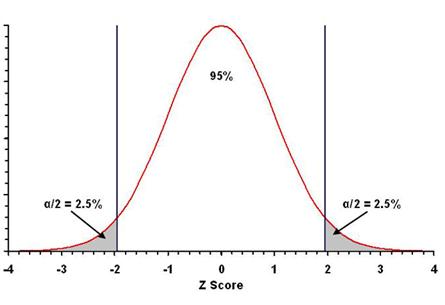

Two-tailed tests are used for non-directional

hypotheses.

¨

For mean differences, the test of a non-directional hypothesis

determines whether one mean differs from the other. The direction

of the difference (lower or higher) is not specified.

¨

The total α (type I error probability) is 0.05. Thus, we

need to find the

critical values

between which lie 95% of the statistical values on

either side of the mean. Any observed value that exceeds those values in

either the positive or negative direction leads to rejection of the null

hypothesis.

·

These regions (gray in the figure below) are the rejection

zones: observed values in these zones lead to rejection of the null

hypothesis because the error probability is lower than α.

¨

Since values either too small or too large should

lead to rejection of the null hypothesis, we need to find the “low” critical

value with 47.5% of the values between it and the mean, and we need to

find the “high” critical value with 47.5% of the values between it and the mean

(47.5% + 47.5% = 95% total).

¨

This means that for a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis

test, the error probability is divided between the

two sides of the distribution, α/2 = 0.05/2 = 0.025 on each side, for a

total error probability of α/2 + α/2 = 0.025 + 0.025 = 0.05, or 5%.

¨

For the normal distribution (Z-scores), the values encompassing

95% of the statistical values on either side of the mean are –1.96 and +1.96, as

noted in Topic 5 for a 95% confidence interval (use Table A.1 or

Excel file).

·

What are the two-tailed critical values in the normal distribution

for α = 0.10, 0.02, and 0.01?

¨

As seen in the figure above (and Figure 8.1 in the text), the

critical

values that result in a rejection of the null hypothesis (–1.96 and +1.96) are

in both tails of the distribution. Hence, it is a two-tailed test.

n

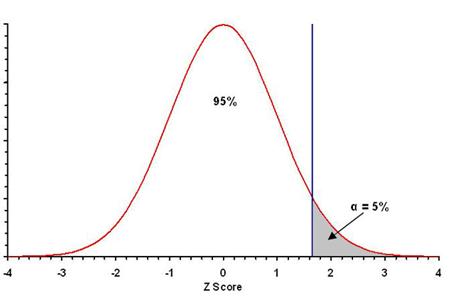

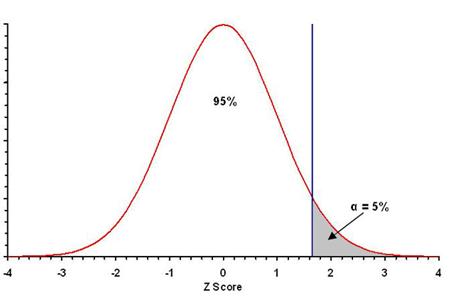

One-tailed tests are used for directional

hypotheses.

¨

For mean differences, the test of a directional hypothesis

determines whether one mean is either higher or it is lower than

the other; the direction of the test (high or low) is stated in the hypothesis.

¨

The total α (type I error probability) is 0.05. Thus, we

need to find the critical value below which lies 95% of the statistical values on

only

one side of the mean. Any observed value that exceeds that value in

the hypothesized direction leads to rejection of the null hypothesis.

·

This region (gray in the figure below if one mean is thought to be

higher than the other) is the rejection zone.

·

Observed values in this zone leads to rejection of the null

hypothesis.

¨

Observations on only one side of the distribution lead to rejection of the null hypothesis.

If one mean is thought to be larger than the other, then we need to find the

critical value on the positive side of the distribution with 95% of the

values less than it (95% total).

¨

The rejection area is on only one side of the distribution, α =

0.05 on the “high” side, for a total error probability of 0.05, or 5%.

¨

For the normal distriubtion (Z-scores), the value with 95% of the

statistical values equal to or less than it is +1.645 (use Table A.1 or

Excel file).

·

What are the one-tailed critical values in the normal distribution

for α = 0.10, 0.02, and 0.01?

¨

As seen in the figure above (and Figure 8.2 in the text), the

values that result in a rejection of the null hypothesis (+1.645) are in one

tail of the distribution. Hence, it is a one-tailed test.

n

The distinction between a one-tailed and a two-tailed

hypothesis is important because:

¨

they represent different research questions, and

¨

they are tested differently.

n

As a general rule, one-tailed tests are preferred unless the

literature and logic provide no reason or rationale why effects would be in

which direction or the other.

¨

Don’t use the wrong test for your hypothesis.

¨

Conduct a thorough search of the existing literature when

developing your research question and hypothesis.

Click

to go to the next section (Section 8.3)

Click

to go to the next section (Section 8.3)

![]() Click to go to

back to the previous section (Section 8.1)

Click to go to

back to the previous section (Section 8.1)

As

discussed above, interpreting ES is similar to interpreting a Z-score.

As

discussed above, interpreting ES is similar to interpreting a Z-score.

![]() Click

to go to the next section (Section 8.3)

Click

to go to the next section (Section 8.3)