This topic has 3 sections.

Reading

n

Thompson and Subar, Dietary Assessment

Methodology.

n

National Cancer Institute, Quick Food

Scan.

n

National Institutes of Health, Fruit &

Vegetable Screener.

Purpose

n

Understand differences between methods of dietary assessments.

n

Understand and mitigate issues with dietary data collection in special

populations.

n

Recognize potential measurement issues with regards to different dietary

assessment methods.

Physical activity is just one aspect of the obesity epidemic, as diet and nutrition are also considered significant factors.

Successful intervention depends on the combination of increased physical activity and diet modification.

The gold standard of clinical treatment is frequent visits with a trained health professional (physician or registered dietitian) during the initial 6 months of therapy.

Researchers usually do not have the luxury of multiple visits to measure dietary intake so additional dietary assessment methods have been developed and validated.

The intent of this

topic is for you to understand the strengths and weaknesses commonly used

assessment methods and to be able to select the best assessment tool for the

situation.

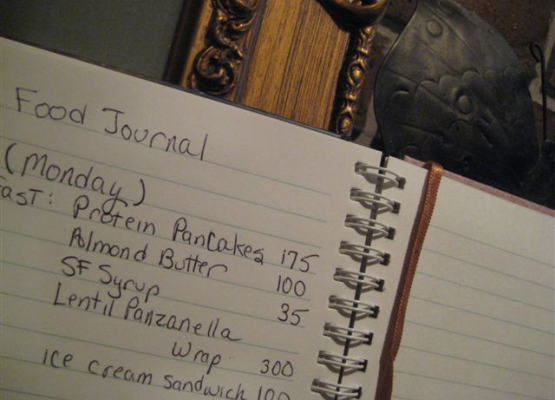

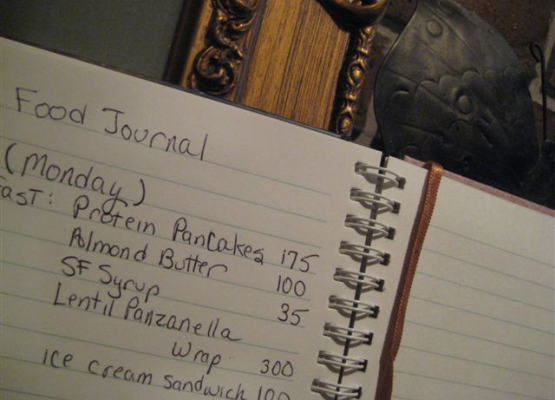

Dietary record

Dietary records are typically obtained for 3 or 4 days. Seven-day records were historically used as the "gold standard" for validating other methods.

But later research showed that the quality of the record actually declines in relation to the number of days recorded.

Additionally, the process of recording food intake can lead patients to change their food-intake patterns.

Food records require literate, motivated subjects and place a high burden on the participants.

The dietary record has the

potential for providing quality data on the type and amount of food consumed,

especially if the record is completed as the foods are consumed.

Some participants will change what they eat drastically during a recording period.

This recording bias is seen as a disadvantage as a typical day is not recorded.

In some situations this is a good problem to encounter.

If the aim of the dietary record is to make the participant aware of

what they are eating and changing that behavior, this “bias” in data collection

can be seen as an advantage.

24-hour Dietary recall

The 24-hour dietary recall was designed to quantitatively assess current nutrient intake.

The 24-hour recall can be conducted in person or by telephone with similar results.

This method requires only short-term memory, and if the recall is unannounced, the diet is not changed.

The method is relatively brief (20 to 30 minutes), and the subject burden is less in comparison with food records.

It is appropriate for use with low-income and low-literacy populations because the subjects do not need to read or write to complete the recall.

Disadvantages of the 24-hour recall include the inability of a single day's intake to describe the typical diet.

The success of the recall depends on the memory, cooperation, and communication ability of the subject.

Also, a trained

interviewer is needed, thus increasing costs for the assessment.

Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ)

The food frequency questionnaire approach is most commonly used in groups of people to provide estimates of usual dietary intake over time (typically 6 months to 1 year).

They are often used in large cohort studies to place individuals into broad categories along a distribution of nutrient intake.

The FFQ lists specific foods and asks the participant if they eat them and if so how often and how much they eat.

Hence, the FFQ must be culture-specific, i.e., different lists of foods have been developed for assessing the diverse diets of such groups as Hawaiians, Japanese, Chinese, Filipinos, and whites.

Both short

(60 food items) and long (100 food items) FFQs have been developed, but neither

were designed to assess current energy intake, an important component of diet

therapy for obesity treatment.

Brief Assessments and Screeners

For some research and/or public health purposes a full-length questionnaire is not practical. Therefore, brief assessments and screening tools have been developed, usually to assess just one or two nutrients or food groups. They generally do not include portion size, but just ask about frequency. Most of the focus in brief instrument development has been on fruits and vegetables and fats, but others have been developed for protein, calcium, sugar sweetened drinks and other food intake.

Both the National Cancer

Institute’s Quick Food Scan and the

National Institute of Health’s Fruit &

Vegetable Screener are examples of brief assessments and screeners.

Diet History

A dietary history is a structured interview method consisting of questions about habitual intake of foods from the core (e.g. meat and alternatives, cereals, fruit and vegetables, dairy and ‘extras’) food groups in the last seven days. This is followed by a ‘cross check’ to clarify information about usual intake in the past 3, 6, or 12 months, depending on the aims of the assessment.

Traditionally it would include a 3-day record which is often now omitted, or may be replaced by a 24-hour recall.

Usual portion sizes

are generally obtained in household measures and / or the use of photographic

aids.

The development of the dietary history is usually attributed to Burke (1947).

The method is a detailed retrospective dietary assessment used more often in clinical practice than in research studies.

A diet history is used to describe usual food and/or nutrient intakes over a relatively long period e.g. 6 months and typically one year.

A major strength of a diet history is its assessment of meal patterns and details of food intake over a long period of time.

Frequently details of how food is prepared are included in a diet history and these details can significantly help in characterizing a diet (frying vs. baking foods).

A weakness of diet history as an assessment method is the participant must make decisions regarding the usual foods and amounts of foods eaten.

Additionally, the food history can have a high burden on the

research team in interpreting the data.